This is the text of my paper delivered at a New Technologies in Renaissance Studies panel at the 2019 Renaissance Society of America meeting in Toronto.

Introduction

Despite my title, I am not a futurist. I am a born optimist who looks forward to many things, but more in the aspirational more than the predictive sense. As the great Wayne Gretzky used to say, I try to skate where the puck is going, rather than where it is.

So in this paper I’ll take a brief look backward at Iter’s history, and its organization of information that becomes knowledge that becomes wisdom about history. Then I’ll look forward to its future in the conjoined realms of discovery and dissemination, and in the realm of collaborative “spaces for possibility and play,” in Liz Grumbach’s words this morning.

But first. Thanks to Bill Bowen, Ray Siemens, and Laura Estill for convening this panel, for inviting me to present on the future of Iter and above all for their leadership toward its next milestone.

A Look Backward

To read Iter’s history, in reverse chronological order online, is to read a history of steady growth: starting with conversations 25 years ago between Konrad Eisenbichler, Bill, and the RSA’s John Monfasani; incrementally expanding to catalogue more and more records of published knowledge about the Renaissance; earning Delmas after Mellon after Delmas. Those who were involved know well how the inside story is much more complex, more fitful, and more uncertain than the official story.

But at the milestone we’re marking now, two decades after Iter’s incorporation as a non-profit, Iter is a mature version of its former self. Similarly, so are many of us.

In my time, I was a front-desk RA and then a fellow at the Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies around the turn of the millennium. I had found my way (courtesy of David Galbraith) to a rickety cage on an interior mezzanine of the E J Pratt library, filled with dusty books and a bronze Erasmus bust. Once I talked them into giving me my first RAship (prodded by Konrad, interviewed by Bill and Nick Terpstra, and funded by Iter), I remember my first day: going through a stack of periodicals (the glossy British magazine History Today) tagging its articles with Library of Congress metadata. That was the first of many days.

Around the same time, George Steiner in a CBC Radio interview recalled that as a schoolboy in Paris, his teachers said that in a lifetime of striving, he might someday add a tiny scratch to the wall of culture. If the Iter Bibliography is that wall, my own scratch is very tiny. Yet today, I feel some satisfaction that some of its 1.3 million citations are mine.

Information > knowledge > wisdom

The story of Iter is a story of striving: striving to describe and catalogue the state of knowledge about the middle ages and the Renaissance, that era and those places that compel our attention.

Each of us is here today because we contribute to that knowledge. Each of us who research and teach medieval and Renaissance cultures owe our professional mission to the methodical work of countless others before us, scholars who compiled and cross-referenced details about books and manuscripts so we could discover what to read next.

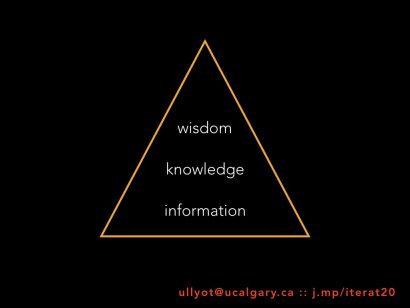

Our knowledge relies on well-organized pieces of information. As this pyramid crudely represents, information about this time and place is vast; our knowledge about it is smaller, and depends on information; and our wisdom about it is even smaller, and relies on knowledge.

If we are very smart and very lucky, one of our published insights might someday aspire to the level of wisdom. (Most won’t.) Few can lay claim to all three levels, as someone like Paul Oskar Kristeller did. His Iter Italicum listed nearly 3,000 humanist manuscripts, while his books on Renaissance thought were both knowledgeable and wise.

Kristeller’s finding list is one of Iter’s many resources. Today’s digital platform serves the purpose that yesterday’s lists and short-title catalogues served. And yet — it serves that purpose not in the sense that it does the same thing, faster, like a concordance; but in the sense that it turns their information into data. With later born-digital assets, Iter Community develops them and Iter Press reviews and publishes them.

Discovery, dissemination, collaboration

Iter fosters three practices: the discovery of knowledge through databases, like the flagship Iter Bibliography; the dissemination of knowledge, by publishing books, journals, and data; and collaborations between knowledge-makers, in Iter Community.

In the second half of this paper, let’s cast a look forward at each of these practices, to chart a course for Iter in the future of our discipline. That future depends on our work compiling information and building knowledge; it depends on our scholarship in 2019 and beyond. The future of our discipline will be shaped by Iter’s role in new knowledge projects: namely, developing and publishing the new information that becomes knowledge that becomes wisdom.

A Look Forward, on Discovery & Dissemination

Iter’s future depends on our answer to this question: How will knowledge about medieval and Renaissance culture and history be communicated and codified in the coming decades?

In 2007 Ed Folsom declared the database the definitive genre of our time. Publishers who blur boundaries between knowledge and the information that (as it were) informs knowledge are responding to the way we work now. They recognize the DH community’s openness about our methods, sharing not just the outcomes of our own process but the methods and the data that enable other outcomes.

Let’s be a little more concrete. Iter can and should continue publishing research data, and connecting them to research outcomes: journals and books. It should connect methods with outcomes, and information with knowledge, as much as possible. Scholars can then oscillate between the two: use and repurpose methods and data to confirm or challenge outcomes.

As Ray Siemens said in our morning conversation, Iter can rethink what publishing means. It it archival, or interim? Planned obsolescence, or open and provisional? The answer is a complementary, hybrid structure that merges information with knowledge; books and journals with data.

There are other ways Iter might change in the coming decades. I’m no futurist, like I said, but I imagine machines will get better at analyzing natural language; it’s not hard to foresee a process using the item-level metadata in Iter Bibliography to teach better topic models of scholarship than Goldstone and Underwood did of the PMLA archives in 2006. When topic models use a controlled vocabulary of item-level metadata, say the Library of Congress subject headings, they’ll enable far more useful results.

A Look Forward, on Collaboration

What future can we anticipate for Iter Community?

Scholarship in 2019 is social: it relies on our collaborations, combinations of knowledge, our shared enterprise. Social scholarship is not some emergent feature in 2019; conferences like this have a long history of hosting and convening scholars.

A platform like Iter Community extends that history into the realm of data. It’s both an incubator for hosted projects and a repository. It’s right to focus on project development and data hosting, rather than trying to be all things to all scholars.

For instance, to replicate Humanities Commons’ social-knowledge platform would be a mistake. The RSA itself has tried to make an online community of its own members, with limited success. But premodern digital humanists are no different from humanists at large: our success depends on the fruitful exchange of ideas, and you can’t do that in an empty room. You go to the panel that’s standing-room only, not the one next door with more speakers than audience.

Ray spoke this morning about the If You Give a Moose a Muffin method: in which small acts of support open larger doors. I’ll echo that children’s book reference with this Frozen reference: “Love is an open door.”

What makes a community is an open door, a shared domain, and shared methods. Common inquiry, and common interests in a knowledge domain.

And what builds that community is a commitment to welcoming new members into the conversation, by sharing our methods. Tom Scheinfeldt once memorably called digital humanists “the golden retrievers of the academy.” We’re amiable. We teach each not just what to know, but how to know it, how to discover new things.

Iter Community needs more of that: methodological openness, welcome mats. I like the screencast idea, and I even volunteer to do one. But I also like the narrative approach of brief, welcoming blog posts. I learned my way into DH in the era of high bloggery (if that’s a word): an era when every self-respecting project spoke about how it built itself, how it developed and changed, how it expanded, how it made knowledge from data. I may be wrong, but I see fewer works-in-progress today than I did back in 2012; the methods-blog seems no longer to be a requirement for DH practitioners.

Conclusion

Like Uncle Toby in The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, each of us has our own hobby-horse. No surprise that mine is methodological openness. So I’m no futurist, but I am a polemicist, and I say: up with methodological openness! (That slogan won’t fit on a laptop sticker.) More publications floating like rafts on oceans of data! (As sea-levels rise, that life-raft is a dystopian simile.)

Iter can be those things. By building on the work of its past, it can be integral to the future of scholarship.